In March we celebrate Women’s History Month. In honor of the month the Special Collections Department takes a look at women’s suffrage. With the enactment of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution on August 26, 1920, by Secretary of State Robert Lansing women in the United States gained the right to vote. In the 100 years since the number of women who vote has risen steadily. According to the Census Bureau in the 2020 election a higher percentage of women voted than men.

In March we celebrate Women’s History Month. In honor of the month the Special Collections Department takes a look at women’s suffrage. With the enactment of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution on August 26, 1920, by Secretary of State Robert Lansing women in the United States gained the right to vote. In the 100 years since the number of women who vote has risen steadily. According to the Census Bureau in the 2020 election a higher percentage of women voted than men.

The women’s suffrage movement grew out of the broader movement for women’s rights. The women’s movement developed in the United Kingdom and inspired Mary Wollstonecraft in 1792 to pen her pioneering work called A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. In the United States in 1838 Sarah Grimké published her widely circulated The Equality of the Sexes and the Condition of Women. Margaret Fuller’s 1845 work Woman in the Nineteenth Century was a key document in growing American women’s movement. The women's rights movement, and, indeed, the women’s suffrage movement was strongly supported within the progressive wing of the abolitionist movement. William Lloyd Garrison, the leader of the American Anti-Slavery Society, said "I doubt whether a more important movement has been launched touching the destiny of the race, than this in regard to the equality of the sexes".

The first women's rights convention was the Seneca Falls Convention, held on July 19 and 20, 1848, in Seneca Falls, New York. The meeting was attended by over 300 women and men. Prominent among those who organized the convention were Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Many who attended were also staunch supporters of the abolition movement. Speakers at the convention advocated for women’s rights and women’s suffrage. Angelina Grimké asked attendees, "Are we aliens because we are women? Are we bereft of citizenship because we are the mothers, wives, and daughters of a mighty people?” Her sister Sarah Grimké declared that “whatever is morally right for a man to do, is morally right for a woman to do.” Other speakers at the Seneca Falls included William Lloyd Garrison, Lucy Stone, and anti-slavery campaigner Abby Kelley Foster. The convention unanimously passed a Declaration of Sentiments. Written primarily by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, it expressed an intent to build a women's rights movement, and it included a list of grievances, including the lack of women's suffrage. The only resolution that was not adopted unanimously by the convention was the one demanding women's right to vote. In fact, it was not adopted until abolitionist and former slave Frederick Douglass gave it his strong support.

The first National Women's Rights Convention was held in Worcester, Massachusetts, October 23-24, 1850. Prominent attendees included Frederick Douglass, Paulina Wright Davis, Abby Kelley Foster, William Lloyd Garrison, Lucy Stone and Sojourner Truth are in attendance. Close ties existed between the Women’s Suffrage Movement and the Abolitionist and Temperance movement. National Women’s Rights Conventions were held, with a five year break during the Civil War, until 1869.

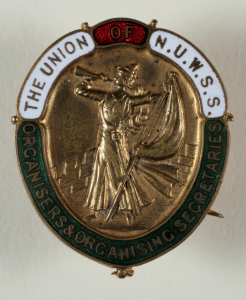

The May 1869 proposal of the Fifteenth Amendment, prohibiting the denial of suffrage because of race, caused a rift in the women’s suffrage and broader women’s movements over the granting of voting rights to black men at the exclusion of women. Ironically, the original language of the amendment included a clause banning voting discrimination on the basis of sex, too. In May 1869 Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and others formed the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA). The NWSA opposed the Fourteenth Amendment and Fifteenth Amendment, in favor of a Constitutional Amendment that would grant the right to vote to all regardless to race or sex. In November 1869, Lucy Stone, Julia Ward Howe, Henry Blackwell and others, formed the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). The AWSA supported the Fourteenth Amendment and Fifteenth Amendment, but supported a state by state approach to achieving suffrage for women.

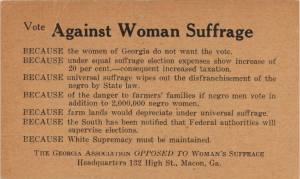

Over time the views of the competing women’s suffrage associations grew closer. In 1890 the two organizations merged as the National American Woman Suffrage Association. The new organization grew more conservative. The leadership of the organization maneuvered through the 1890s and early 1900s to accommodate the politics of white supremacy in South. Susan B. Anthony asked Frederick Douglass not to attend the NAWSA convention in Atlanta in 1895. In 1903 black NAWSA members were excluded from convention in the city of New Orleans. And, by 1903, despite the early close alliances between the women’s suffrage and abolitionist movements, the NAWSA endorsed a policy of supporting “states’ rights,” or the rights or powers retained by states rather than the national government.

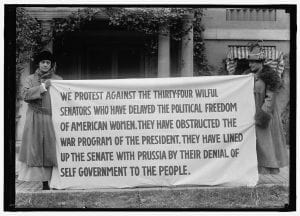

There were men, and women, opposed to women’s suffrage in every region of the country. Both men’s and women’s anti-suffrage organizations existed. In fact, anti-suffrage organizations existed in every state. There was opposition from brewers and distillers organizations that grew from the close relationship between the women’s suffrage movement and the temperance movement. Southern anti-suffrage groups were organized. While the suffrage movement backed away from links with the abolition movement, the anti-suffrage movement made it a focus of their campaign. In Georgia Mildred Rutherford, president of the Georgia United Daughters of the Confederacy and leader of the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage made clear the opposition of elite white women to suffrage in a 1914 speech to the state legislature: “The women who are working for this measure are striking at the principle for which their fathers fought during the Civil War. Woman's suffrage comes from the North and the West and from women who do not believe in state's rights and who wish to see negro women using the ballot.” Henry Browne Blackwell was among those who urged the suffrage movement to pursue a strategy of convincing southern political leaders that they could ensure white supremacy in their region without violating the Fifteenth Amendment by enfranchising educated women, who would predominantly be white. The fear extended beyond just black women voting and extended to "lower orders" of former slaves and immigrants. As Elizabeth Cady Stanton wrote in an article on page 266 of the April 29, 1869, issue of the Revolution lower orders grew to include Chinese, Africans, Germans and Irish, with their low ideas of womanhood.

So, what about the women’s suffrage amendment to the Constitution? It was actually introduced in 1878 by Senator Aaron A. Sargent, a friend of suffragist Susan B. Anthony. It would take more than forty years to pass both houses of Congress, twice, and be ratified by two thirds of the states. It would eventually become the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution with no changes to its wording. Ironically, its text is identical to that of the Fifteenth Amendment except that it prohibits the denial of suffrage because of sex rather than "race, color, or previous condition of servitude".

So, what about the women’s suffrage amendment to the Constitution? It was actually introduced in 1878 by Senator Aaron A. Sargent, a friend of suffragist Susan B. Anthony. It would take more than forty years to pass both houses of Congress, twice, and be ratified by two thirds of the states. It would eventually become the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution with no changes to its wording. Ironically, its text is identical to that of the Fifteenth Amendment except that it prohibits the denial of suffrage because of sex rather than "race, color, or previous condition of servitude".

A sampling of Fulton County Library System Resources on Women’s Suffrage

Women's Suffrage, Sugarman, Dorothy Alexander

Women's Suffrage, Fact Sheet, by Larson, Elizabeth C. LC 14.23:R 45805/

Women's Suffrage: Fighting for Women's Rights, Isecke, Harriet

The Oratory of Women's Suffrage (video)

She Votes: How U.S. Women Won Suffrage, and What Happened Next, Quinn, Bridget

Founder of the Women's Suffrage Movement, Kent, Deborah

History of Woman Suffrage, Stanton, Elizabeth Cady

Southern Strategies: Southern Women and the Woman Suffrage Question, Green, Elna C.

What 80 Million Women Want (video)

Not for Ourselves Alone: The Story of Elizabeth Cady Stanton & Susan B. Anthony (DVD)

African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote, 1850-1920, Terborg-Penn, Rosalyn

Add a comment to: Women’s History Month – Women’s Suffrage